Finding hope: Iowa Water Conference brings research breakthroughs to the forefront

Brandi Janssen’s professional focus is safer, healthier agricultural communities. Growing up on a farm during the 1980s farm crisis provides her an empathetic view of the economic constraints facing farmers. Her work as a clinical associate professor of occupational and environmental health at the University of Iowa (UI) offers a sobering glimpse at the very real public health threats at play in rural America. Therein lies the dilemma: two valid perspectives that are often not in alignment, particularly when it comes to managing our stressed waterways.

Iowa has the fastest-growing rate of new cancer cases in the nation, according to Iowa Cancer Registry data. A growing body of research is connecting drinking water contaminated with nitrates, arsenic, and other heavy metals to numerous chronic diseases, including cancer. Meanwhile, robust water treatment facilities to protect drinking water are out of reach for many cash-strapped rural communities.

Janssen, the keynote speaker of the 18th annual Iowa Water Conference, challenged that we may be able to find solutions if our society reframed its thinking to waterways as “the commons.” It’s a resource too large and too important to be privatized, she noted.

“Think of your connection to the river,” Janssen said. “What stories and connection points do we have?”

Janssen presented the approach taken in Slovenia, which has a blue spaces campaign for health and well-being. Rivers there are viewed as a place to be cherished for providing clean drinking water, recreational opportunities, and beauty, and thus the country embraces protecting rivers.

Janssen’s keynote speech embodied the theme of the conference, “Life Depends on Water. Water Depends on You.”

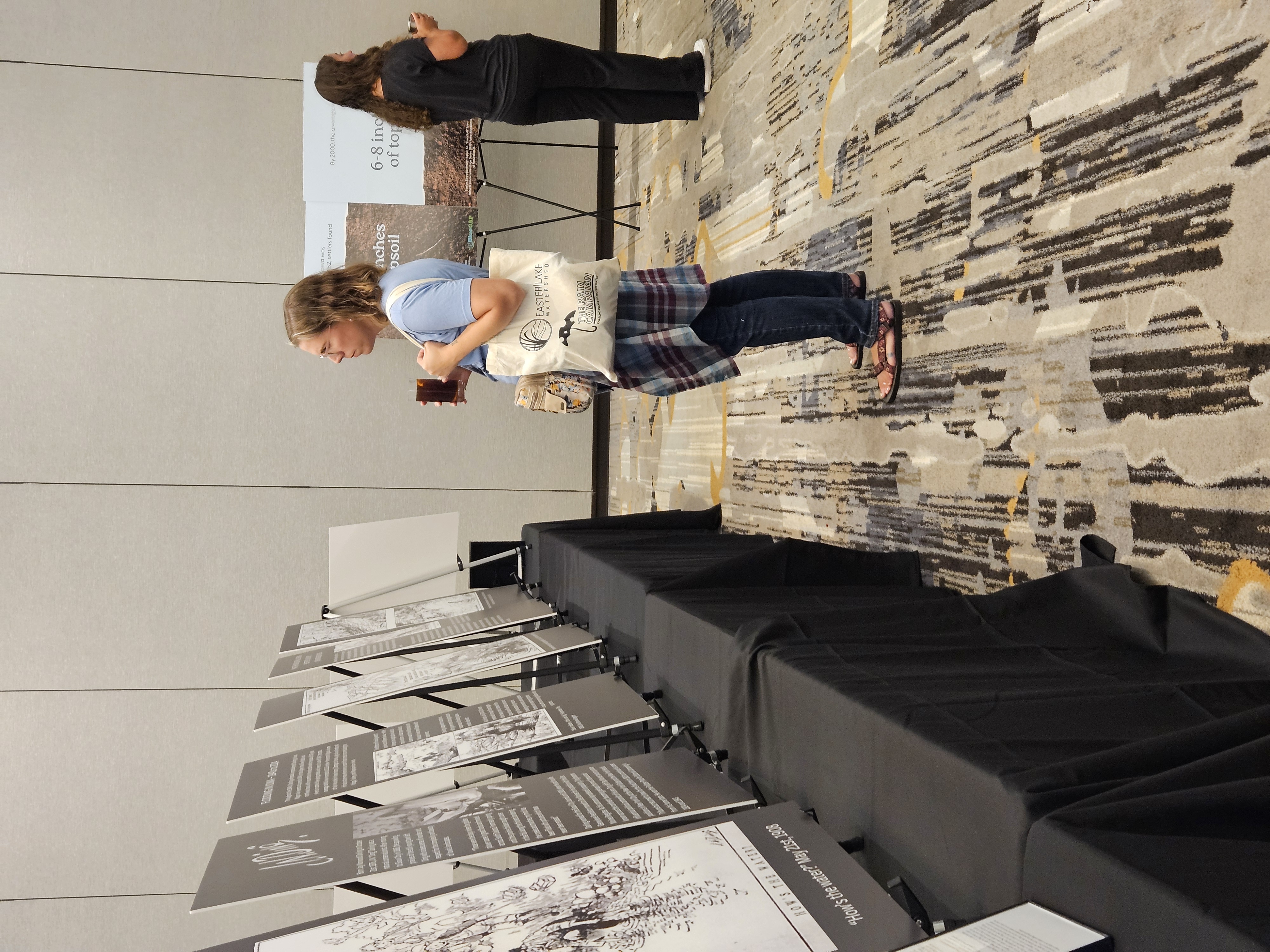

Held at the Hyatt Regency in Coralville, September 11-13, the conference drew more than 300 attendees running the gamut of Iowa water resource professions, including representatives from soil and conservation districts, research institutions, commodity associations, watershed compacts, and nonprofits.

“The goal is to provide an opportunity for stakeholders throughout the water world of Iowa to network, share research, and find out how they are handling issues in their communities,” said Laura Frescoln of the Iowa Water Center at Iowa State University and a member of the conference planning committee.

A highlight this year was a University of Iowa art exhibition, in which artists, writers, and scholars put a face on the impacts of nitrogen pollution in waterways and watersheds though their medium. The project is part of the National Science Foundation-funded Blue-Green Action Platform, or BlueGAP, which aims to connect communities across watersheds to address economic and health challenges caused by nitrogen pollution in their water and local environment.

This year also featured a tour of the Johnson County Historic Poor Farm, which was established in 1855 as a home for Iowans with mental illness, disabilities, or financial problems. Today, the 160-acre farm provides a platform for many user groups to test sustainable food production, nitrate and bacteria removal strategies, flood mitigation tools, watershed management, and land stewardship all while honoring its history.

“The Johnson County Historic Poor Farm allows us to show the impact we are making with new conservation practices and the many different partnerships that have come together,” said Kate Giannini, program manager for IIHR—Hydroscience and Engineering and Iowa Flood Center as well as member of the Iowa Water Conference planning committee. “Having the farm so close to campus gives an opportunity for students and faculty to get involved in research, whether biology, social justice, or engineering.”

A Wicked Problem Panel focused on “collaborative conversations for climate-resilient watersheds.” Including Jack Stinogel, V Fixmer-Oraiz, Humberto Vergara, Catherine DeLong, Sarah J. Gardner, and Clark Porter, the panel balanced perspectives of a farmer, research engineer, elected official, water quality professional, hazard mitigation planner, and climate coordinator. Following a panel discussion, attendees broke into small groups to workshop topics.

Panelist Vergara is a UI assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and an IIHR research engineer focused on hydraulic modeling for flood forecasting. He advocated the need for more data collection resources to support current and future projects.

“We have done a lot of work in the state of Iowa, but we are not done,” Vergara said. “We can’t just use what was developed 10 years ago forever because the human-natural system is in constant change. We need to create new products of information so we are always up to date and capturing important changes.”

Greg LeFevre, a UI associate professor of civil and environmental engineering and research engineer at IIHR, led a session examining cutting-edge stormwater research. LeFevre has been characterizing enzymes in fungus that may help break down chemical compounds found in stormwater. He likens the research using DNA-based characterization of fungal communities in green stormwater infrastructure to “stormwater CSI.” In another NSF-funded project, LeFevre’s team has developed a novel, patent-pending geomedia for stormwater green infrastructure systems that rapidly capture toxins in water during infiltration and then biologically degrade the chemicals as a pollutant removal strategy.

Frescoln, from the Iowa Water Center, said one of the reasons the conference has been so successful is not only discussing the current state but learning about what is on the horizon for solutions.

“We often get discouraged as a group trying to improve water quality in the state,” Frescoln said. “Being able to go somewhere where positive things are happening is a real inspiration.”