IIHR—Hydroscience and Engineering is an internationally renowned laboratory where researchers are solving some of our world’s greatest fluids-related challenges.

Rivers, Watersheds, and the Landscape

IIHR researchers are addressing issues related to sustainability in the water, energy, and food nexus; improving our understanding and adaptation to climate change; increasing community resilience to natural hazards; and helping equip society with the tools to make informed decisions.

Fluid Mechanics and Structures

Fluid mechanics, the study of fluid behavior at rest and in motion, is at the core of nearly all IIHR research. IIHR uses the basic governing equations of fluid mechanics to investigate a wide range of applications—river flow, atmospheric conditions, renewable energy (e.g., wind and water turbines), ship hydrodynamics, biological systems, and much more.

Health and the Environment

Much of IIHR’s research touches all our lives, affecting human health and well-being in meaningful ways. Studies of biofluids, environmental contaminants, vulnerability, and resilience are relevant to each of us. In addition, projects on renewable energy and watersheds help remediate society’s negative environmental impacts, leading to a higher quality more sustainable life.

Information Systems

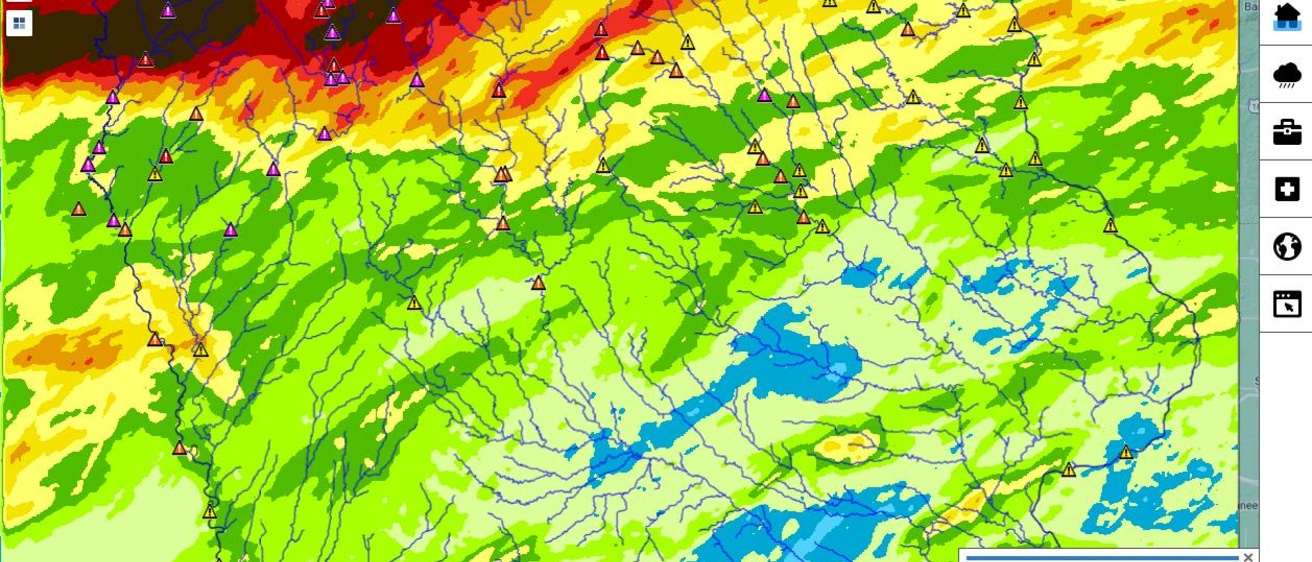

Beginning with the innovative Iowa Flood Information System (IFIS) in 2011, IIHR has made online public access to research data the standard for its major research initiatives. IIHR has developed online data access systems for water-quality information, flood mitigation projects, well-driller information, and more. These platforms provide emergency managers, decision-makers, and the public with reliable data.

Serving Iowans

From flood to drought, surface water to groundwater, IIHR is helping Iowans understand and manage water resource challenges to ensure a livable and sustainable future.

Student Success

Research Impact

Recent News

Understanding Our Aquifers

Iowa could be on the cusp of a hydrogen rush; lawmakers weigh regulations

Stern Wins Regents Award for Faculty Excellence

Events

Environmental Advocacy Day

Join us! Support Iowa's environment and the health of all Iowans.

IIHR—Hydroscience & Engineering and the Iowa Flood center will be joining the Iowa Environmental Council's Environmental Advocacy Day to discuss research and tools that are helping Iowans prepare for extreme weather, including floods, droughts, groundwater, and water quality challenges.

This event is free and open to the public, but registration is required.

We hope to see you there!

Danville Family STREAM Night

You're invited to the Danville Family STREAM night on Tuesday, March 3!

Danville's family STREAM night will bring together students, parents, and community members for an evening of hands-on learning, exploration, and inspiration. Local businesses and organizations will provide STREAM-related activities for families to participate in. The Iowa Flood Center will be hosting a table, displaying their interactive watershed model that educates Iowans on flooding in order to keep our communities safe.

W...